This essay is adapted from a lecture given to Mark Pollard’s Sweathead community in July 2023. Special thanks to Ben Perreira, VÉRITÉ, Black Dave, Shukri Lawrence, Nikita Walia and Joan P. Ball, PhD for helping me develop this piece. All credit to Domingo Beta and VÉRITÉ for creating the visual objects featured within. As a follow up, I’m planning to host a workshop in NYC and more virtual conversations on these themes soon – if you’re interested in being in the loop, hit me up.

Introduction

“How do we tap into culture?”

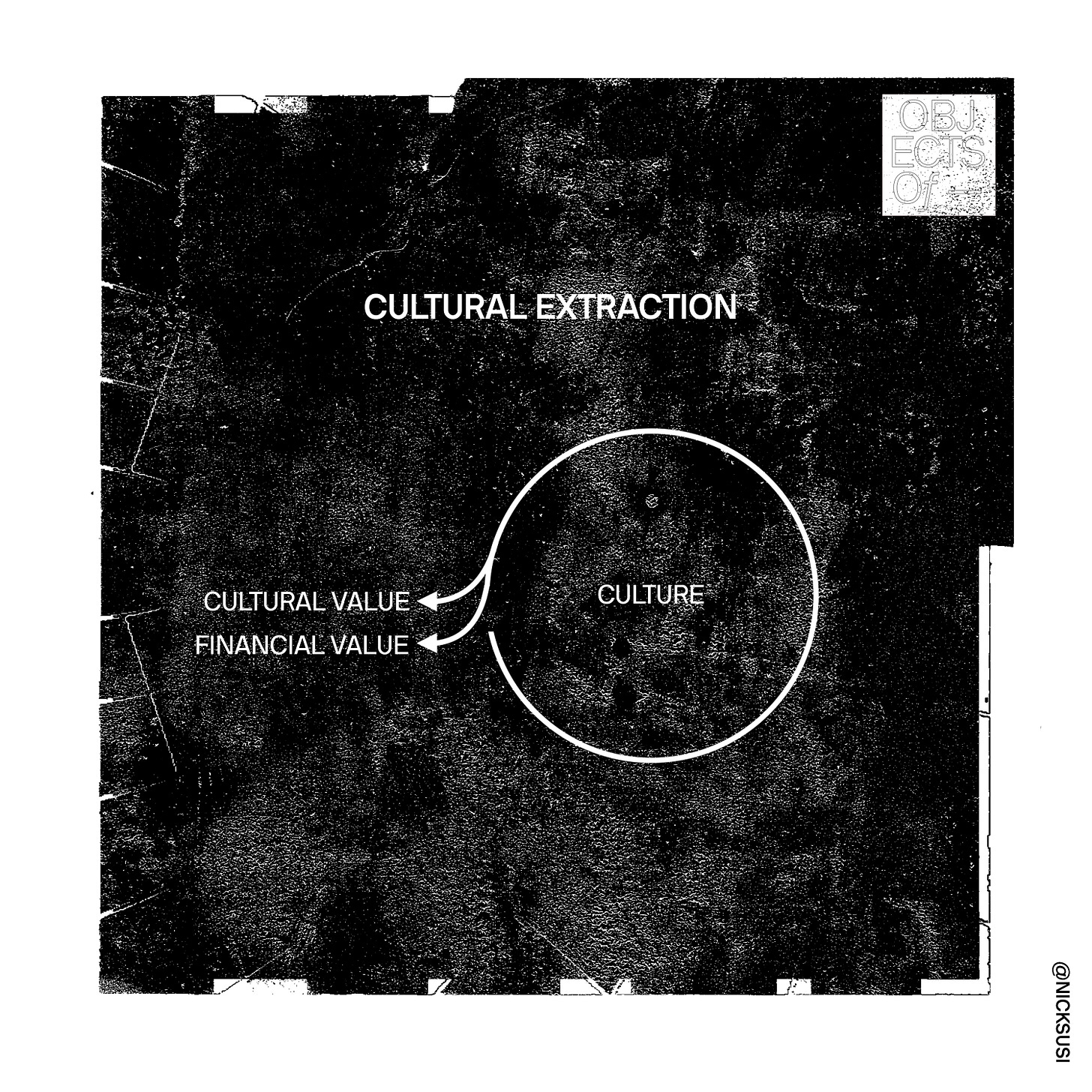

I hear this question often. It always makes me think about the “How do you do, fellow kids” meme of Steve Buscemi playing a cop, trying to infiltrate high schools and entrap students. What does this question about tapping into culture even mean? Too often that tapping of culture is extractive – extracting value from a culture, without providing value back.

How can we design better systems, a new social contract even, of mutual cultural exchange? Ones where we collect and apply cultural knowledge in a way that’s most mutually beneficial and sustainable for the people of a culture?

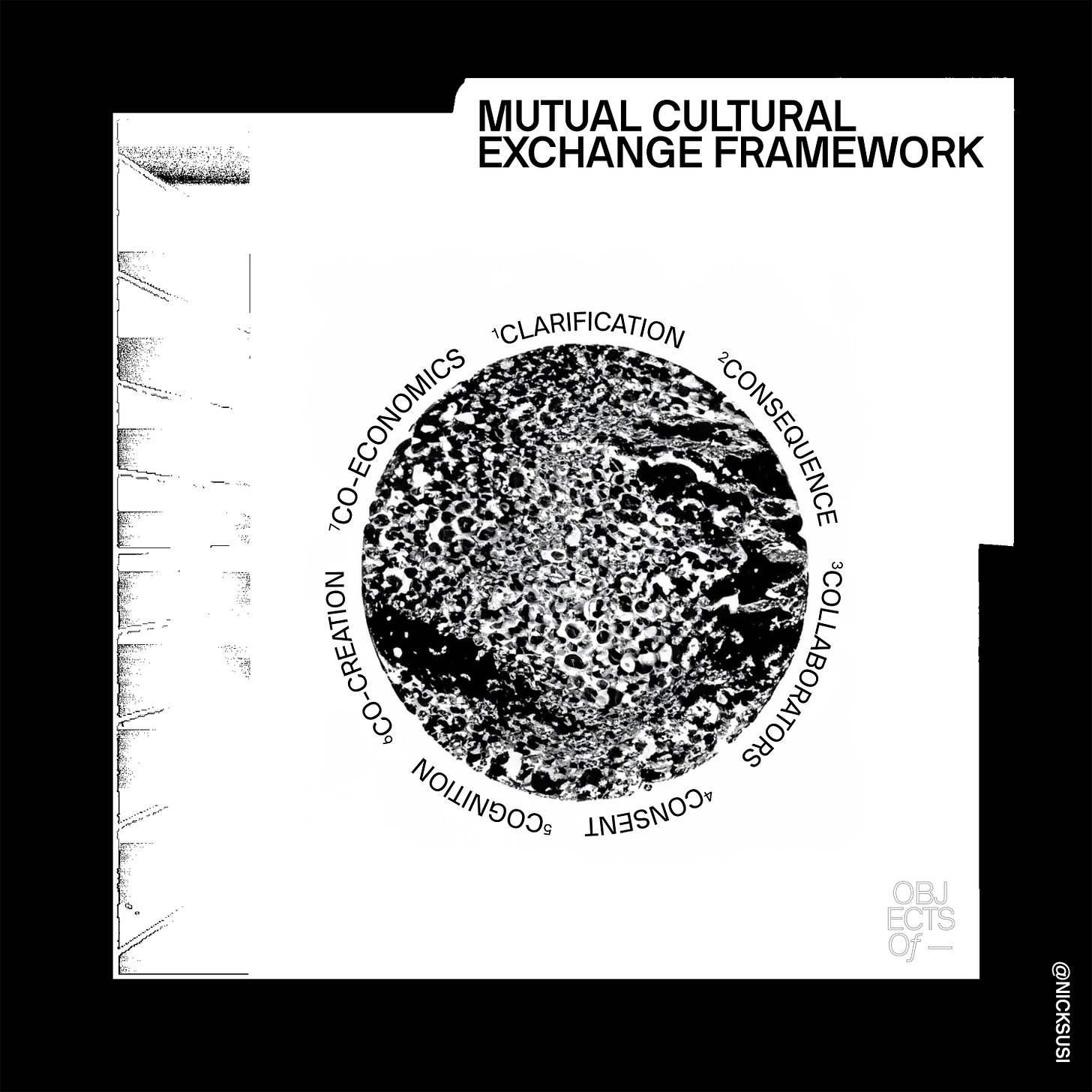

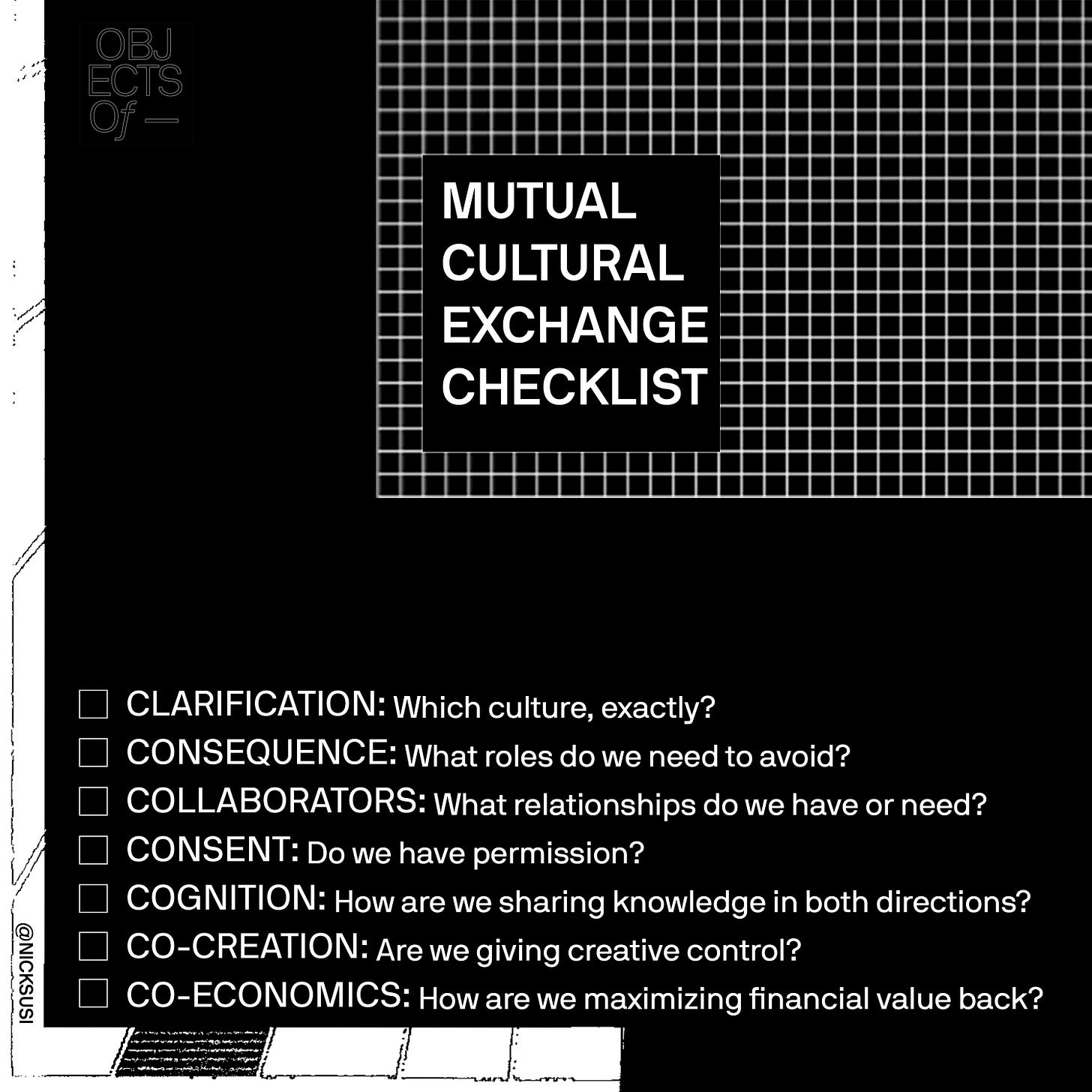

1. Clarification

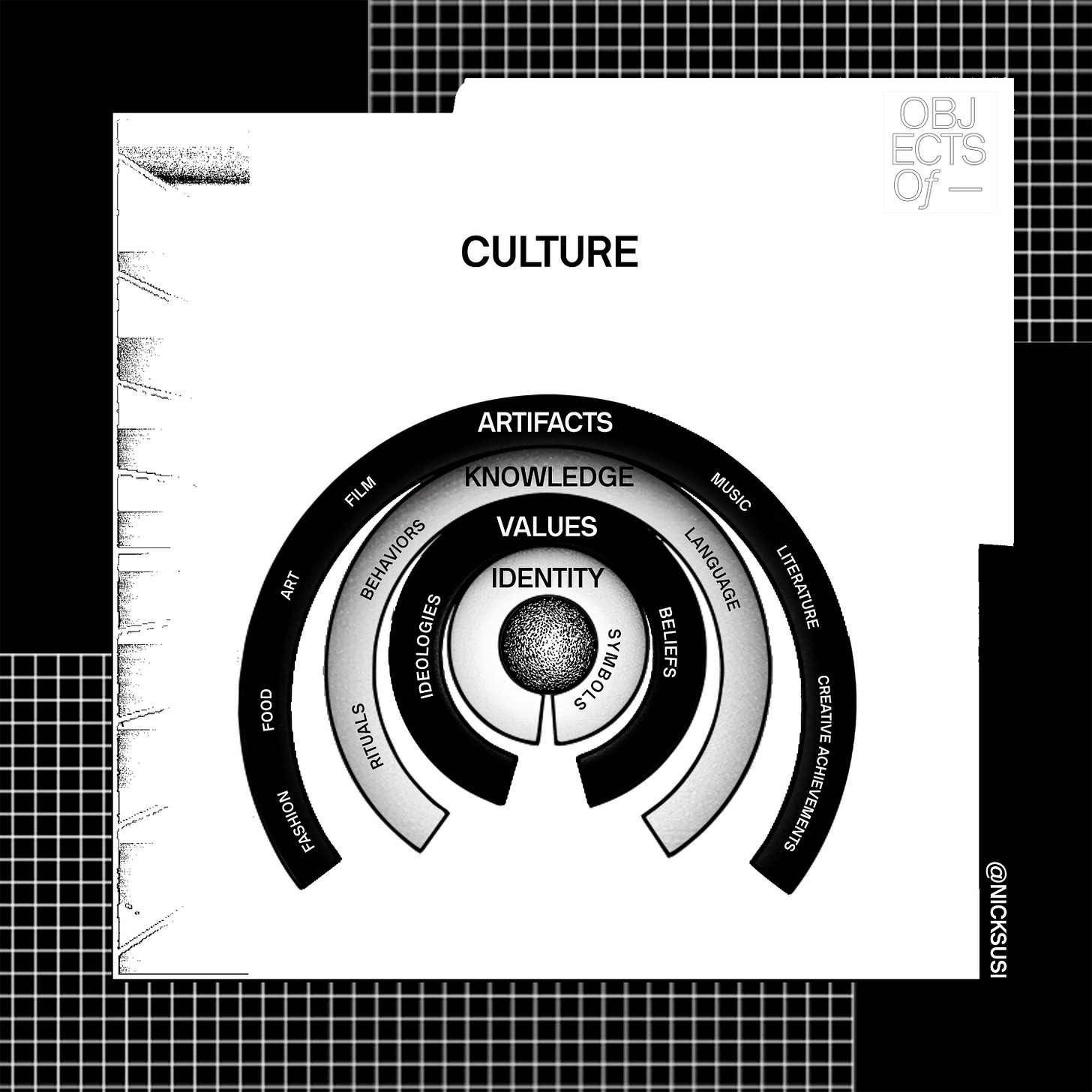

“Culture” is suffering from semantic satiation – it’s one of those words that’s so overused, it’s lost its meaning. So to define it:

Culture is a shared set of elements that characterize a group of people – a religion, a race, a society, a movement, a scene.

Tapping into culture needs to be more than, how do I make my brand cool? Cultural strategy is the act of understanding, contextualizing and applying cultural knowledge to achieve an intended outcome or change, in a way that respects, benefits and sustains the culture of origin. The last bit is arguably the most important aspect, yet unfortunately, the most overlooked.

There are so many different cultures, so the first, most important question to ask is:

Which culture are we talking about exactly?

Drill culture? Web3 culture? Southern California skate culture? The culture of independent artists?

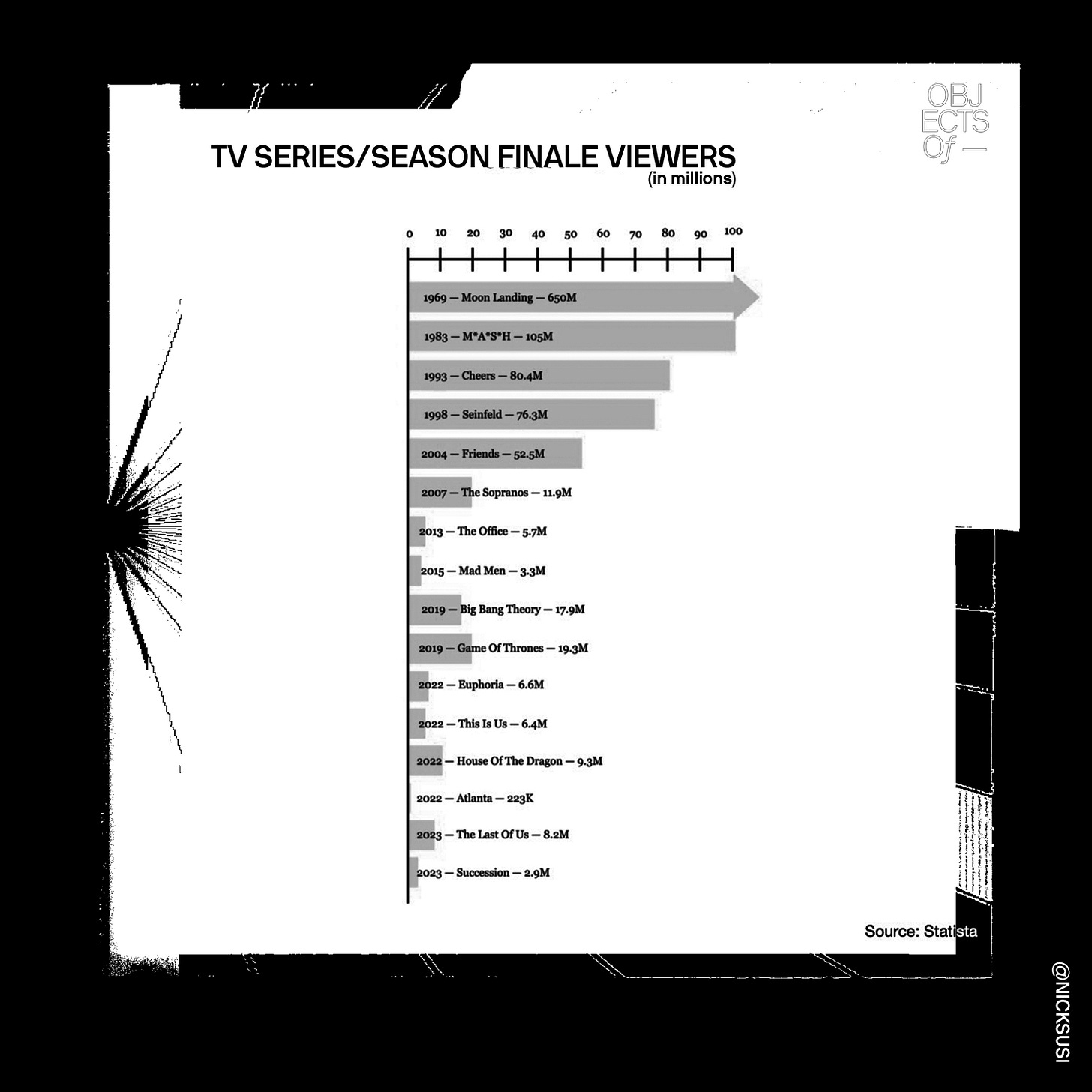

Earlier this year, Succession on HBO came to a close. For many, the series finale felt like a massive cultural moment. The reality is, however, that connective tissue that TV show finales provide us has drastically declined over the past several decades.

Whether or not monoculture is truly dead is less the point here – but it is true that culture is increasingly fragmented. Our algorithmic feeds on social media are becoming more and more niche and harder to follow. We’ve all heard people make cultural references that we have no idea what they’re talking about. Saturday Night Live even had a sketch about it earlier this year.

We can’t tap into culture if we don’t truly know or understand the specific culture we’re trying to tap into.

2. Consequence

Too much of this tapping into culture is exploitative appropriation – withdrawing and redirecting the value of a culture away from the culture itself, for financial gain, without substantive reciprocation, permission and/or compensation, regardless of whether or not that was the original intent. This becomes particularly problematic when there is a power imbalance, where one dominant culture is reinforcing its dominance over another.

Let’s take a brief look at history.

Gentrification

Can different cultures integrate equitably without changing the fabric of cultural identity?

Harlem has been a major capital of Black American culture – but as wealthier individuals and businesses have flocked into the neighborhood, it has pushed money out of the community and into commercial development. Property value has skyrocketed. It’s made housing unaffordable for many, and has forced the displacement for many original residents and businesses. Since the 1980s, the Black population has continuously decreased, while the White population has shot up exponentially by 10x. As the original residents become displaced, there’s a loss of connection to their cultural identity and their social bonds with the community.

Tourism

Can cultural values sustain if not upheld consistently?

In 2019, over 10 million tourists entered Hawaii – which is more than 7 times the state’s entire population. While this generated nearly $18 billion, the majority of that money goes to large corporations that aren’t owned or run by local residents or native communities. This drives up the cost of living, and pushes locals out of their homes. It has an ecological impact too. Now, over 60% of the plant and animal species in Hawaii are endangered. While all tourism isn’t necessarily bad, over-tourism can have a devastating impact if not managed sustainably.

Biopiracy

Do the originators of cultural knowledge benefit from how it’s applied?

Throughout history, many pharmaceutical and food companies have attempted to essentially own indigenous cultural knowledge of biological resources and how they’re applied. They have attempted to patent, commercialize and monopolize the cultural knowledge of resources like turmeric, aloe vera, and as of today, psilocybin-based therapy. This is done so without consent, involvement or fair compensation of the original community. This is biopiracy. It’s the Christopher Columbus’ing and plagiarizing of cultural knowledge. The problem is, when these companies are successful in doing this, they cut off the local community from accessing and applying these resources that they’ve already been nurturing and preserving for hundreds of years. The economy of the community becomes constricted, while the cultural knowledge is leveraged elsewhere to form a company worth hundreds of billions of dollars. For example, Australia’s bush food industry is booming as a result of Indigenous cultural knowledge and how it's applied, but only 1% of the dollar value generated makes its way back to Indigenous people.

Museums

Do the creators of cultural artifacts benefit from their display?

Various archaeological studies estimate that in some museums, anywhere from 70 to 90% of the cultural artifacts that they have in their possession lack documented provenance. This means that how the artifacts were acquired is unknown, which means they could be and in many cases definitely are stolen. For example, in 1897, the British forces stole the Benin Bronzes from the Kingdom of Benin, which is now a part of Nigeria. Since then, many of them have been on display at museums like the British Museum of London and The Met in NYC. These cultural artifacts are important pieces of Nigerian history and culture, but have been severed from the local communities that they originate from. They’ve never been able to see them, and it has contributed to a loss of cultural sovereignty. Yet, by holding and showcasing cultural artifacts, many of which have been looted, in the US alone, the museum industry has grown to $11 billion.

What does this have to do with the desire to build a cool brand?

This is an invitation to pause and reflect. These are the patterns across the long arc of history. When we desire to collect and apply cultural knowledge, what role might we be playing?

When it comes to brands, trying to tap into culture the wrong way can have irreparable consequences for everyone.

Dolce & Gabbana vs Chinese Culture

In 2018, Dolce & Gabbana launched a tone-deaf ad campaign that depicted a Chinese model struggling to eat Italian food with chopsticks. This was made worse when the co-founder Stefano Gabbana doubled down on the ad. The backlash was immediate. #boycottdolce went viral. Chinese consumers burned their products on social media. Chinese actors and models canceled runway shows and terminated their brand deals. Its products were pulled from major Chinese e-comm retailers. The brand went completely dark on Weibo for over three months. But most interestingly, the reaction wasn’t a fleeting moment. Five years later, the brand still struggles to win back Chinese culture. Social media engagement in China dropped 98%. No mainland Chinese celebrities have signed with the brand since. The brand has had to close 20% of their stores in China, and remains frozen out of some of the biggest e-comm retailers.

If you fuck with a culture, the culture will fuck with you.

Punk, Then & Now

Even in cases where we’re successful in our application of cultural knowledge for commercial gain, that doesn’t mean that it leaves the community in the same or a better place. For example, the punk movement. In the 70s and 80s, from British punk to Afropunk to Queercore, the subculture’s original ideologies were clear. It represented individual freedom, anti-establishment, DIY, anti-consumerism. But over time, punk was ultimately mainstreamed and co-opted. It was diluted down to just edgy aesthetics and symbols, fashion and hairstyles. But it was disconnected from the people and values it originated from. It’s become a product of hyper-consumption, which is ironic considering its anti-consumerism origins. Fast fashion brands like H&M and Urban Outfitters sell punk clothes. Sex Pistols merch continues to proliferate across the internet. A teenager exploring their identity on Reddit earnestly asks r/punk, “Do I have to be completely anti-consumerism to be punk?” Granted, the mainstreaming of the underground is part of the natural life cycle of a subculture – and the internet has only accelerated this cycle at lightning speed. But it becomes tricky when commercialization is involved. Take Dr. Martens. It became the iconic brand that it is today because it was adopted by the punks of the 70s and 80s. So when the brand reaches the level that they’re at now, and sells to private equity for half a billion dollars, how do we make sure the culture that made the brand mutually benefits too?

What is the role that we play when tapping into a culture? Are we contributing towards it thriving sustainably? Or are we accelerating its lifecycle towards its fragmentation or end?

How do we design better systems, or even a new social contract, where everyone wins?

Acting in the best interests of a culture is acting in the best interests of a commercial endeavor. It’s all about sustainability and risk management. Cultural extraction is not sustainable – it may get short term rewards for one, but has severe long term risks for all. Mutual cultural exchange is sustainable – it takes short term bets together, but has long term rewards for all.

3. Collaborators

A few years ago, a homegoods brand came to me looking for support. They wanted to show that big life-changing moments can happen right from within one’s home. To do so, they wanted to tap into music culture on TikTok. Specifically, young aspiring artists that sing into their phones from their bedrooms. They wanted their role to be helping to find the best talent and getting them signed to a record deal.

Here’s how they got to the idea. They conducted ethnographic and netnographic research, scrolling through TikTok and speaking to consumers to better understand their interests in music and emerging artists. They spoke to their in-house music team, as well as executives at major record labels for guidance. But there was one fundamental flaw. They explored how they could best design for their brand, as well as for their consumer, but they never stepped into the culture itself to speak to artists. Not aspiring artists about what they need most. Not established artists about what their journey was like in their earliest stages. The brand wanted the value of music culture, but they were wholly disconnected from the cultural producers of it, their values and their needs. Instead, the relationships and conversations that led to this idea were from the outside, with industry-assigned experts.

This led to a critical missing detail – in the earliest stages, independent artists should remain independent as long as possible. They often don’t want to or need to sign to a label. Signing too early can often ruin their lives and careers, getting locked into long term contracts and debt. One thing that artists do need in the early stages is significant co-signs from other bigger artists that don’t come with any strings attached. So what if instead of signing them to a deal, the label provided the biggest artists on their roster to duet on top of bedroom artists’ TikToks, giving them an organic co-sign and boost, all with the homegoods brand at the center of the moment? Deeper collaboration with artists wouldn’t have just benefited the artists, but it would have led to better, more interesting ideas and diversity of thought for the brand too.

We need to operate like culture is the client.

If a culture is our client, are we talking to the right people? If we’re talking to no one, that’s definitely not enough. Could you imagine working with a client that you’ve never met or talked to before? American society in particular pushes us to compete as individual experts of cultures. But our role is better served as collective advocates, especially if there’s a power imbalance or if a culture is not entirely our own.

This emphasis on being an individual expert often keeps us in the mindset of the gentrifier, the tourist, the plagiarist, the looter. It’s through this mindset that we take knowledge out of a culture through more passive education, observation and immersion. We consume books, articles, TikToks, podcasts. We observe behaviors and conversations both online and off. And then we repackage the knowledge we’ve gained, commercialize it and benefit from it.

If we never make an effort to reach out and form real relationships with the origin sources of where we’re gaining valuable cultural knowledge for ourselves, how do we know if we have consent? How do we know if that value chain ever connects back to them?

To be clear, there is unique value that we can provide in our ability to curate, synthesize and apply cultural knowledge from elsewhere, but as we see with this homegoods brand and many others like it, our role needs to go further.

Instead, as collective advocates, we should be creating open doors and pathways for our relationships within a community to flow in.

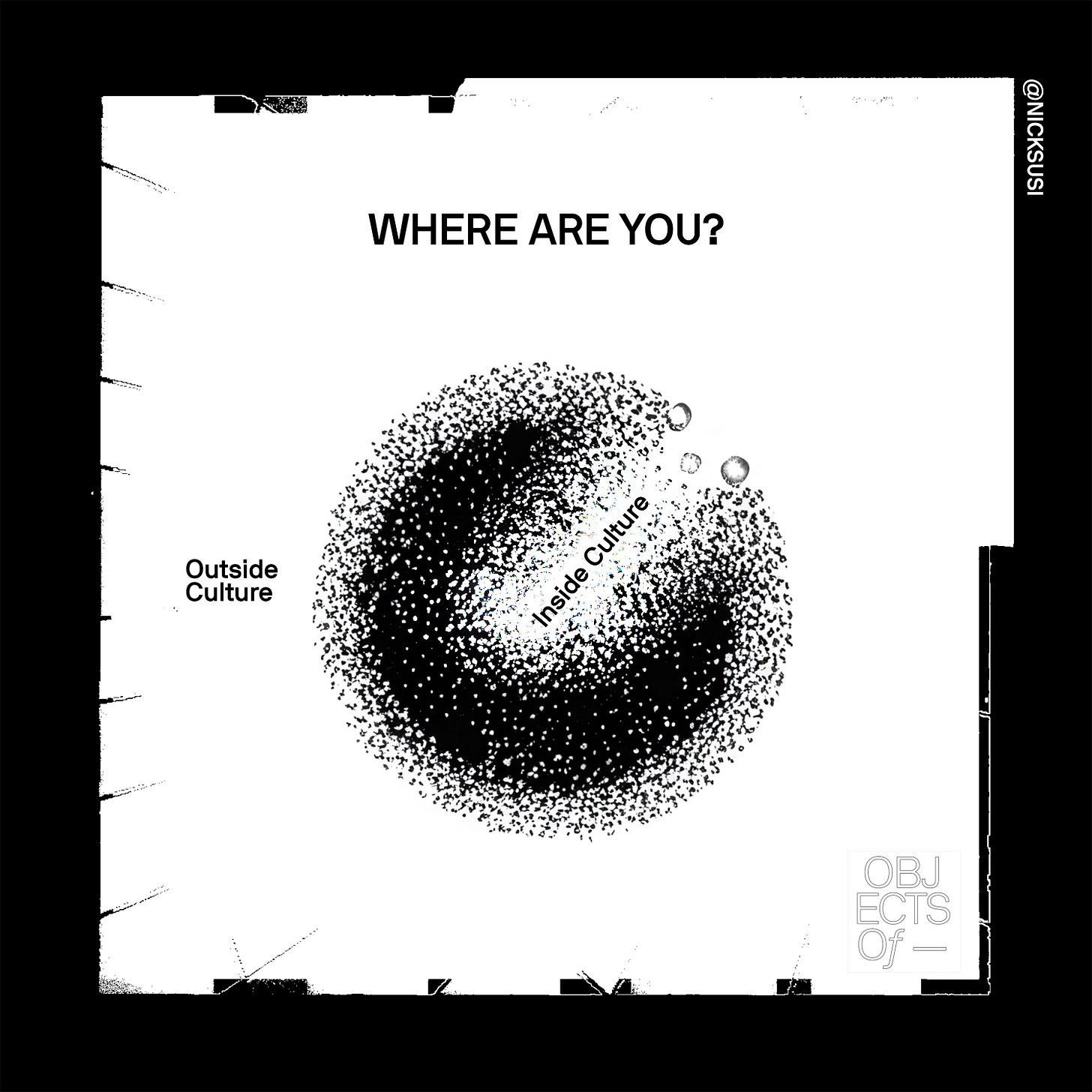

There’s also a difference between making relationships with individuals inside vs outside of a culture. We need both. Talking to well-studied individuals who are outside of a culture looking in is definitely a valuable and essential part of the process of sensemaking. But it does not replace the depth, proximity and nuance that comes from talking to and forming relationships inside of communities that originate cultural knowledge.

Our relationship with a culture shouldn't look like a scientist peering through a microscope.

If we just passively observe from the outside, and don’t we don’t form direct, active relationships with the leaders, artists, elders, people with lived experiences that make and change a culture, how can we truly be an expert or an advocate?

Further, if we’re talking to consumers, it’s important to understand the distinction between talking to consumers of a culture, vs the people within a culture.

We’re in a bizarre time where two different things are true at once. The internet and globalization makes transculturation - the complex homogenous mixture of elements of multiple cultures - even more difficult to identify what community is the origin of cultural knowledge. But also, as mentioned earlier, the internet and social media continues to fracture cultures and communities down to niche geographies on and offline. So it’s important to make the effort to find the source, and look out for power imbalances too.

In a world where information is so easily and readily open and accessible through search, social and now LLMs (large language models), the real relationships that we have with people who hold insider knowledge across different cultures and communities becomes our competitive edge.

Mutual Cultural Exchange

So how do we push this from theory into practice?

Last year, Jacquemus wanted to host their Spring/Summer fashion show in Hawaii. It was going to be their first show outside of France. The location was inspired by a previous Jacquemus campaign in Hawaii. They wanted to support the connection they felt with the people there. But how should they approach it the right way? They called my friend Ben Perreira – co-founder of passionfruit alongside his partner Taylor Okata. Perreira is a creative director and stylist from Hawaii that’s worked with LVMH and Virgil Abloh.

They started by assembling a local team. From planning and ideation to execution and marketing, their community relationships flowed through every touchpoint of the process from the very beginning. They had full creative control, and were trusted that it would lead to the best, most authentic experience. Intention fueled every decision of the fashion show. From who they hired, to the local models featured, to the local music played, to the local food served, to the gift baskets provided by local weavers, filled with locally sourced fruits, flowers and reef-safe sunscreen.

For the show itself, they used a simple blue runway on the beach, instead of a set that would have obstructed the natural surroundings, or even damaged them. At one point in the evening, they gave a native Hawaiian blessing. But it was important to the community that the sacred moment wasn’t commodified, so no one was allowed to record it with their phones. Clear lines were drawn for where the brand could and couldn’t play to fully respect the culture.

The impact was tremendous for both the culture and the brand. Every decision maximized the money flowing back into the community vs away from it. Hundreds of people worked on the show, most of which were hired locally. Everyone involved was paid the higher industry standard rate, instead of the much lower local standard. The blending of the local community with the broader global creative world created new economic opportunities too. Amine loved DJ Tittahbyte’s set so much that he invited her to perform the opening set of a future show. SZA loved the chef, Andrew Le, so much that she hired him. Bianca Kei, one of the local native Hawaiian models, became featured in a Skims campaign.

For Jacquemus, the show took the brand to a new level. The show became the highest Google searched moment to date for the brand at that point last year (March 2022).

But it also created a ripple effect across the industry too, inspiring a new precedent. Later in the year, Chanel and Pharrell Williams went to Dakar, employing a similar model with the Senegalese culture and community that centered them in a fashion show and put long-term partnerships in place with local craftspeople.

Overall, was it perfect? No. Hawaii still faces the same challenges and impact from over-tourism. But the level of detail on how to best maximize the value back to the community is an important model. It treats the community as a true collaborator, rather than people to sell to or commodify.

[Author’s note: About one week after giving this lecture in July 2023, wildfires devastated Lahaina. To support the local community, passionfruit launched a fundraiser t-shirt, supported by Jacquemus, among other fashion brands like Braindead and Cactus Plant Flea market, and raised $30,000+ for those impacted.]

4. Consent

In order to apply cultural knowledge with the most credibility and authenticity, we need consent, especially if a culture is not entirely our own.

In order to get permission, we need to go beyond our interest in trends, passively educating ourselves, showing appreciation and even giving credit. We should do all of these things, but this alone is not enough.

It needs to push further and get into the details of every aspect, from start to finish.

Relationships from within a culture must be a part of the process. True long-term relationships — not just short-term transactions. Perreira and Okata of passionfruit were the perfect bridge builders, because they understand both the culture of fashion and Hawaii so well, and their network of relationships allows them to dive even deeper into the community.

Not every brand can have permission – and that needs to be respected. It depends on the brand, it’s history, the power dynamics between it and the culture.

5. Cognition

Passive observation from the outside is not enough. Bi-directional, circular knowledge exchanges are key.

If there’s valuable cultural knowledge that we are looking to gain, what unique valuable knowledge do we have that we can also share back? How can we open source research, mentorship, education, connections?

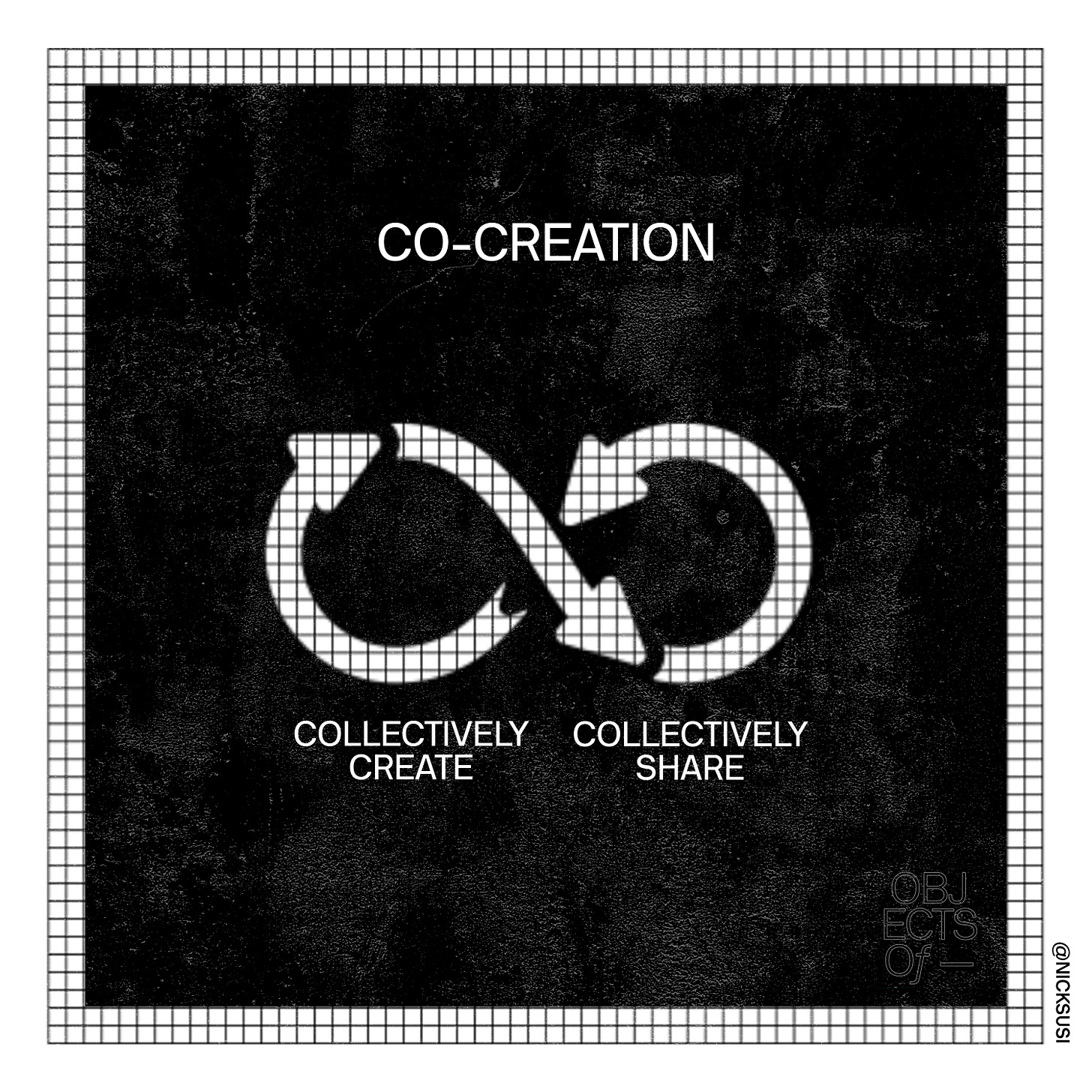

6. Co-Creation

Creating for a culture, without the involvement of a community, or forcing what to create upon them, won’t work. The process of collaboration needs to be open and co-developed.

Real creative control should be put into the hands of a community — not just performative optics internally or using people as props externally. A safe environment is imperative for everyone to raise concerns for sensitivity or accuracy of how cultural knowledge is applied. The collaborators should be able to choose how their community is featured and credited.

7. Co-Economics

Collaborating with a community through Cognition and Co-Creation, but without Co-Economics, isn’t enough. The promise of free exposure is not enough either.

From insight to ideation to execution, how much of the budget and future revenue is going to make its way to the people who lead and produce the specific culture that is being tapped into vs going elsewhere?

In Closing

The best way to approach this will always be case-by-case and context dependent.

But if and when you have the desire to tap into culture… don’t be Steve Buscemi.

Nick Susi is a writer and strategy executive, exploring the forces - technological, societal and psychological - that shape our identity, perception and culture. He has led strategy for dotdotdash, Complex, The Fader and Jay Z’s former media brand Life+Times. His research and writing can be found in Business Of Fashion, Friends With Benefits, Water & Music, Matt Klein’s ZINE, Joshua Citarella’s Do Not Research, Future Commerce and Boys Club.

Great read, thanks! That Jaquemus example was very instructive.. the faux-pas they did not commit tells a lot: "At one point in the evening, they gave a native Hawaiian blessing. But it was important to the community that the sacred moment wasn’t commodified, so no one was allowed to record it with their phones. Clear lines were drawn for where the brand could and couldn’t play to fully respect the culture.

As a musician/artist/writer/reader, I am very interested, but I'm fairly far from the cutting edge of all this. I see at least a dozen facets of this post that I believe deserve a separate article: The 7 C's, the headings under "Consequence", the roles of the Cultural Extractor, and more. If you ever get time, I think the bite sized posts like that would help engage people like me. I'm ready for more, though all I can pledge is time, right now. Best wishes!