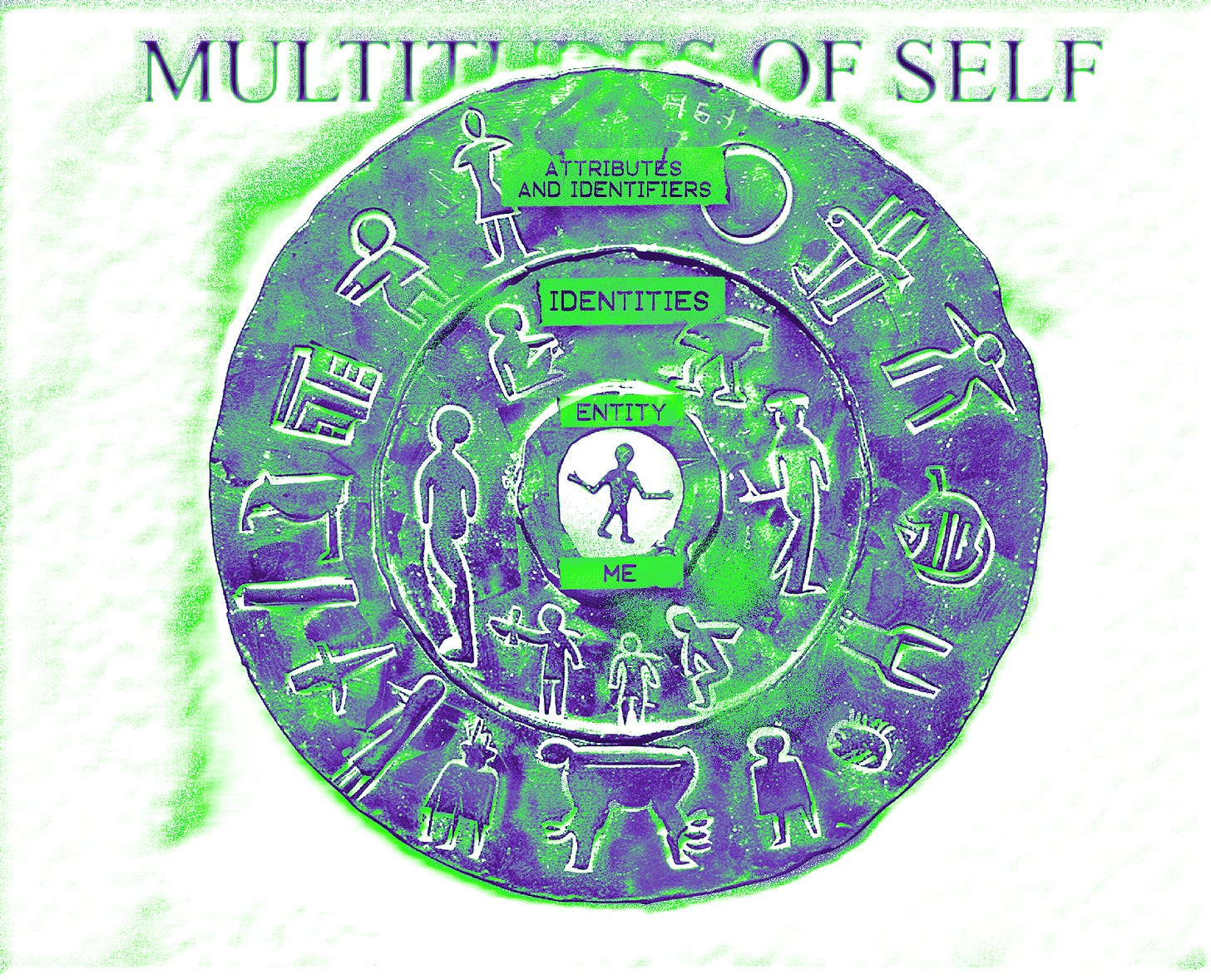

the multitudes of self

reflections on identity

This essay was originally written for Veleta Studio Lab’s zine Atemporal. Special thanks to Joan P. Ball, PhD, Tiger Dingsun, kianamoods, Matt Klein, Yana Sosnovskaya, Yancey Strickler and VÉRITÉ for helping me develop this essay. All credit to Domingo Beta for creating the visual objects featured within.

1 : Identity Compression

How do I be all of me?

Last year, author Jessie Gaynor wrote an essay about grief in Dirt. In it, she discusses infant loss influencers on Instagram – “women who define themselves, at least for public consumption, by unimaginable grief.” Many of these accounts have solely curated their entire public personal brand around what I imagine to be the worst moment of their lives.

I had a similar thought watching Netflix’s Baby Reindeer. I wondered what it would be like for Richard Gadd, the creator, to spend years writing and acting within a one-man theater show and a television series, reliving the experience of being stalked and abused over and over again.

To be clear, it is not for me to judge how others process grief or trauma. Everyone does it differently. Through TikTok (GriefTok), Instagram, Reddit and other platforms, both creators and viewers have been able to connect with a community of people who understand what they are going through better than their own immediate friends or family. They feel less alone. They feel seen.

But the commodification of grief as identity on social media is very real. The algorithm can serve us catharsis, but it can also haunt us, nudge us and optimize us and our identity towards staying within the infinite attention and engagement loop of creating and consuming grief content.

I was diagnosed with cancer at the start of this year. Almost every person I’ve told has asked me what I’m going to write about it. How has it changed my perspective? When am I going to share the news? All I can think of in response is how badly I do not want to be compressed into “cancer guy” online. I feel this constant wariness of Identity Compression – the reduction of one’s identity into a singular, self-reinforcing focus, maintained over an extended or permanent period.

How can we say something deeply personal online without it becoming our entire identity? How can we share parts of ourselves with the world without creating an expectation for more of the same type of content? How can we communicate online without losing control over how the narrative around our identities can be pigeonholed, or even ripped apart, by both humans and the algorithm based on how they perceive it?

As human beings, we are multitudes. We have many sides to our identity – the elements that define and distinguish our sense of self. As futurist Tracey Follows describes, we are prisms.

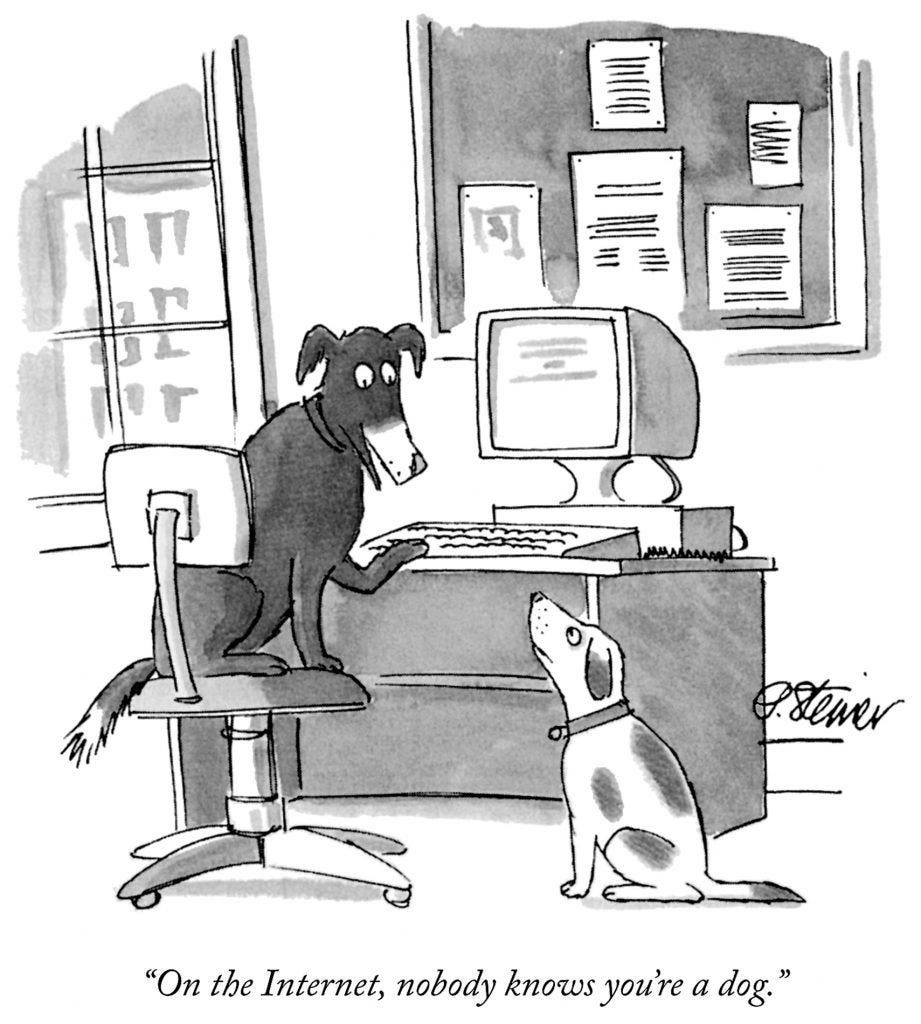

The supposed promise of the internet has been that we can explore, discover and fully crystallize our identities into these unique, multi-sided prisms in ways that we never could offline. We could become anyone.

Or, more importantly, we could be anyones – intricate identities with limitless depth and surfaces reflecting pieces of ourselves back into the world.

“For individuals before the internet, the key existential question was ‘Who am I?’ After the internet, it’s ‘Who all am I?’”

In reality, however, the systems we live within — both algorithmic and societal — often push us towards the opposite. Through Identity Compression, it feels like being tossed into an industrial crusher – reduced to the grieving parent, the cancer guy. We are forced to pick a singular lane and consistently craft our personal brand, package ourselves into a product and appease the repetitive, insatiable appetite of the algorithm. If we do this successfully, we can grow our audience and reap the rewards of financial and social capital.

This is the winning strategy for competing in today’s Olympic games of status, attention and individualism. But what is sacrificed and lost when we’re not all of ourselves?

“Once we worried about the ownership of things. Now we worry about the ownership of self. [...] We give so much of ourselves away - intentionally and accidentally, through personal data, profile creation and performance. Today’s media sucks us in and spits us out, copies, pastes and pixelates us until we aren’t even sure who we are any more.”

We seem to be caught between this moment of thought provoking theory and speculation about how technology like AI, blockchain and new modes of social media will shape the future of identity, vs the practical realities of the anxiety and overwhelm that we experience as humans today.

Granted, these things are not mutually exclusive. We can navigate both simultaneously, but more often than not, these systems around us silently nudge us towards the epicenter of this strain.

It’s not just the algorithm. Wrestling with being boxed into singular roles, and trying to break from them, is not unique to digital spaces. Our class systems. Education systems. Criminal legal systems. Work culture. The advertising machine. Religion. Nationalism. All that surrounds us pushes us towards these rigid boxes of identity.

The way our identity shifts and multiplies from context to context — family, friends, work, school, relationships — is not new.

But like all things, technology is an accelerant. The algorithm is a mirror that amplifies all of this at increasing speed, volume and scale. As we look to the future of identity, what happens if we continue to compress – or multiply – ourselves? How do we ultimately find balance as we attempt to discover, express, maintain and answer, how do I be all of me?

2 : Identity Dysmorphia

How do we build reputation without the side effects of status games and infinite scale?

Audience Capture looms around us. We’re stuck in a never-ending feedback loop, telling our followers what they want to hear to keep their attention, but unable to evolve beyond our meticulously crafted personal brand, our Identity Compression.

“So many of our actions (i.e. performances) are pre-evaluated with the question: How may this impact me forever? This drives a lot of loud, performative activism, but also quiets us in ways. The only thing worse than censorship is self-censorship.”

To make matters worse, when our digital selves extend beyond our immediate following into the public arena, we risk facing the hostile environment that the internet has become. Dunking. Cancel culture. Tribal-fueled verbal assaults.

“Did we sign up for this type of scrutiny by strangers just by being on these platforms? Do we deserve it? Do we consent to it? Or is this just a feature that we have to implicitly accept? [...] Now that platforms serve content to a broader, more amorphous network of internet strangers, our identities are somehow both more fluid, yet more vulnerable to being calcified into forms that could spiral out of our grasp. Despite our best attempts at controlling our stories, any trace of self-mythology can be hijacked and re-canonized into lore that belongs to the network.”

Libby Marrs & Tiger Dingsun, “The Lore Zone,” Other Internet

Some of us are retreating to our cozy, private corners of the internet – back into the dark forest. Some of us are logging off. But even as we reenter meatspace to escape this arena and touch grass, we’re still confronted with the peculiar side effects of our blurred digital-physical reality. Through the status games that we play online, many are placing more weight on how to build reputation around the digital self, sometimes at the expense of our physical surroundings and relationships.

SoHo continues to be littered with TikTok NPC streamers annoying passersby. As I take a break from writing this essay to walk around McCarren Park in Williamsburg, I see a pair of women with a camera and a microphone wearing shirts that say “ORGANIC DOG MEAT,” chasing unsuspecting, non-consenting people through a farmer’s market, trying to capture viral moments of themselves coercing others to start eating vegan.

It’s not just strangers affecting strangers, though. It’s permeating into our closest, most intimate relationships.

Perhaps this is even more of a bombshell than me outing myself as cancer guy, but I’m also a former recovering Instagram boyfriend. Freya India’s recent essay on the topic hit home:

“I don’t think it’s trivial, for example, that we’ve been conditioned to use the person we love as a tool—a tool to gain approval from an audience that most of the time we don’t even like or care about. I don’t think it’s trivial that the compulsion to document the perfect memory can degrade the memory, turning it from that time we watched the sunset together on the beach to that time we argued after I demanded Instagram photos and you couldn’t get the angle right. I don’t think it’s trivial that some people sacrifice their real-world reputation to improve their online one.”

Freya India, “Your Boyfriend Isn’t Your Camera Man,” After Babel

I know someone with a dozen secret finstas. I discovered that when they post on their main public account, they would spend hours logging in and out of their finstas to like and comment on their original post to boost the algorithm. This process in itself is not an issue. If you’re going to play the status games, play them well. But what was more puzzling was when I asked them about it, they denied it and had a meltdown. The admission would shatter the illusion constructed around their digital identity and reputation – something that had grown to become more essential than maintaining their physical relationships and the honesty and intimacy within them.

This feels like Identity Dysmorphia – an obsessive preoccupation with perceived flaws in one’s distorted self-concept.

This is what happens when there are too many eyes watching online, perpetually. Our brains are not meant to handle the pursuit of this infinite scale. I’m reminded of the famous quote by Sartre from his 1944 play, No Exit. “Hell is other people.” Perhaps if he were alive today, he would revise - “Hell is too many other people.”

3 : Profilicity & Digiphrenia

How do we expand our identity without exceeding our capacity?

Remember the viral Dolly Parton Challenge meme? It perfectly captured the constant juggling act we’re in, fine-tuning ourselves to build status and reputation based on who we’re talking to — something a single profile can’t fully address or solve for. Our most professional self. Our most basic self for our family. Our most creative self. Our most dateable self.

Our identity is further fragmenting and decentralizing into different online personas for many different contexts. We are in this constant wrestle between authenticity – expressing who we truly are regardless of how we want to be seen – and Profilicity – a term coined by philosophers Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D'Ambrosio in their 2021 book “You And Your Profile: Identity After Authenticity.” It describes the shaping of identity by curating multiple profiles, based on what others within a larger, personally unknown general public will observe and how they might react.

As our identity fragments and decentralizes more and more, however, we are hitting our limit to what our brains have been designed for.

It leads to Digiphrenia – all credit to Matt Klein for putting me on to this concept. The term, coined by media theorist Douglas Rushkoff, is derived from digi for “digital” and phrenia for “the disordered condition of mental activity.” By creating infinite identities, our fractured attention leads to infinite information overload, ultimately sacrificing our ability to truly connect and be present with the people around us.

This definitely felt true for me at the peak of the last hype cycle of NFT PFPs and DAOs. After creating a couple of pseudonymous accounts and jumping into about a dozen different digital communities, it didn’t take long before I felt extreme burnout and like I was unable to keep up.

Even for those who have never experienced what it feels like to jump from identity to identity online, we have all likely experienced something similar at school or work. The overwhelm of fifty open tabs at once. Constant context switching between different projects and tasks causes stress and neuroticism, requiring over 20 minutes to fully refocus between each and every switch.

Fully becoming prisms is great and all, and perhaps future generations’ brain capacity will evolve with new emerging media environments, but without balance today, we grind ourselves into dust.

4 : Identity R&D

How do we put more choice and control over our identity back into our hands?

We need better approaches for how we as people, not the platforms and systems around us, decide to explore and express our multitudes of self. More control. More self-sovereignty. Ultimately, more choice.

What do we present as public and easily understood by others, vs hide and make illegible to those outside our inner circle?

When do we use our legal name, vs a pseudonym, a private account, an alt, a finsta?

What do we intend to communicate to our immediate connections, vs to unknown strangers?

What do we express online as real, vs a performance? Is there a difference anymore?

How connected is our physical self to our digital self?

Where do we want more coherence between our identities, vs less?

Where is our identity safe, vs at risk of those who are watching or surveilling?

What is our Storied Self – the life stories and experiences that we integrate and internalize into our on-going sense of self in the perceived present?

What is our Temporal Self – the transient aspects of our identity that have been left behind in the past?

What is our Possible Self – the ideas of who we both hope and fear to become in the future?

I love Aaron Z. Lewis’s concept of Identity R&D – an infinite game of playing with and integrating different aspects of one’s identity. He proposes how we might have an alt account that no one knows about for Development, an alt account that our friends know about for Staging, and a main account for Production.

“In time, I got over my ‘stage fright’ and switched a lot of my alt activity to my main account. But just when I thought I’d outgrown my pseudonymous profile, something surprising happened. The act of taking my private thoughts public generated a whole new set of thoughts that I wanted to incubate behind my mask. [...] My alt account is like a satellite that orbits my current identity. It does weird research, plays with uncomfortable ideas, asks dumb questions. Eventually, it sends its learnings back to HQ. New learnings are integrated, and the process of exploration begins anew — ad infinitum.”

Aaron Z. Lewis, “Being Your Selves: Identity R&D On Alt Twitter,” Ribbonfarm

5 : Identity Coherence

How do we integrate and maintain coherence around our present Storied Self – or is this not the point?

I feel grateful to have so many winding, expanding life experiences and affinities.

Practicing visual art and illustration throughout grade school. Making music and playing in bands during my college years at Berklee. Founding a music company and managing artists throughout my 20’s. Going deep into streetwear and sneakers while heading up strategy at Complex. Spending a year living in a Palestinian neighborhood next to Sheikh Jarrah in the middle of the 2021 crisis. Now, playing and experimenting with emerging technologies at dotdotdash.

Each chapter could be a book in their own right. As each experience and affinity expands, especially the ones that have altered my life and shaped the multiple sides of my identity the most, I find myself with the constant urge for Identity Coherence – the extent to which one feels a sense of continuity in integrating different aspects of themselves, including past experiences, present self-perceptions and future goals.

What about that time I was 14-years-old living in a lab in Bermuda amongst scientists, convinced I wanted to be a marine biologist? Or that one time in 2019 that I took a sketch comedy writing course that I thought was going to change my life? Those future Possible Selves that I once imagined are perhaps just parts of my Temporal Selves that remain in the past.

“It feels like a fun fact more than anything else at this point. It’s a defining characteristic that’s been dropped by the wayside and that I’m forced to move beyond.”

But I do continuously find myself trying to connect the dots as they expand. To find coherence. To find integration. To keep all of me together.

“‘Identity is not to be found in behavior, nor—important though this is—in the reactions of others, but in the capacity to keep a particular narrative going.’ This he says is done by continually integrating events in the outside world into our ongoing story about the self.”

Russ Belk on Anthony Giddens (1991), “The Extended Self In A Digital World,” 2013

Perhaps this urge for Identity Coherence and integration is a generational Millennial-coded, Facebook-raised inclination, vs those of younger generations, especially those whose socialization was considerably affected by the pandemic. Or maybe it’s a matter of life stage. Or maybe, it's an innate human desire to keep the most important aspects of myself alive.

Or perhaps, this is a futile effort. Theravada Buddhism suggests that clinging to the aggregation of our multitudes of self, called Skandhas, causes suffering. It is only through relinquishing the desire for this control and embracing the impermanence of the moment that we can find a state of true happiness.

6 : The Fallacy Of Infinite Memory

How do we record memories without losing the true presence of the moment?

To keep our past Temporal Selves pulled into the present alongside our Storied Self, memory is crucial to integrating and maintaining the on-going Identity Coherence narratives of our identity. Philosopher John Locke’s memory theory of personal identity basically posits that the identity(s) we construct around ourselves is within the limits of our ability to recall our past memories. We are what we remember. As our memories disappear, so does our identity. We see this in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s, as well as in those with severe PTSD, like people affected by war or natural disasters, and their difficulty to integrate fragmented memories into a coherent narrative of their life’s story.

Our memory, however, is not infallible. Every time we recall old memories, they can be accidentally altered, overwritten or deleted through reconsolidation, affecting their accuracy and the context of what they mean to us. This is why eyewitness testimonies are not always the most reliable. Longitudinal studies about flashbulb memories – memories about an emotionally or historically significant event – show that more than half the time, every year that we recall the memory, we change the details of where we were, who we were with, what we were doing, despite our confidence in the accuracy of our ability to remember. This also works in reverse. Through narrative therapies, studies show that we have the ability to trigger memory reconsolidation to update the meaning and context of certain memories, and in turn, transform our beliefs about our Storied Self.

If we need better approaches for more control and choice around our identity, do we need better approaches for memory collection and recall?

Using technology for cognitive offloading is not new. We ask our phones and computers to remember information so we don’t have to. We use our cameras to chase perfect moments to commit them to memory. And now, with LLMs, a new form of memory extension is emerging.

“Not everyone saw the development of artificial memory in a positive light. In 1530, the electric physician Cornelius Agrippa cautioned against it: ‘Artificial memory would not be able to last for the briefest second without natural memory… [Artificial memory], by overburdening the natural memory with innumerable images of words and things, can lead those who are not content with the limits imposed upon them by nature to the point of madness.’”

Kei Kreutler, “Artificial Memory & Orienting Infinity,” Summer Of Protocols

While these tools can be effective in extending our memory, studies show they can just as easily diminish our ability to recall memories on our own, especially when the tools divert our attention, take us out of a moment, and away from maintaining true presence – the things that allow our brains to collect and store long-term memories. To be clear, cognitive offloading isn’t a bad thing in every context. We don’t need to memorize every phone number or direction for driving. But how much do we want to offload our life experiences and affinities from our brain that are critical to the construction of our identity?

“Any memory device, is fundamentally an identity device. To be in the business of memory transformation, augmentation, extension, even simply storage — is to be in the business of identity.”

Reggie James, “Memory, Identity & Transformation,” Product Lost

Last year, Google announced its AI-powered Best Take feature for the Pixel 8. Basically, if anyone in the frame isn’t looking at the camera or smiling, the AI can look through previous photos in our camera roll to mix, match and automatically swap past expressions into the current photo to ensure everyone is facing the camera, smiling.

Unsurprisingly, the announcement was met with a wave of AI doomerism. On one hand, it’s understandable to spiral into questioning, what happens when AI can automatically manipulate our photos, and therefore our memories, and therefore our identity? But let’s be real. The idea of editing photos in pursuit of an idealized self or moment is not new. Photoshop. Facetune. The difference here is where the control and choice sits. When capturing and editing becomes one compressed action, instead of two distinct ones. Where is it essential for us to keep certain control and choice in our own hands, and not offloaded to an AI?

On the other hand, despite human memory not being infallible, as Freya India points out in the aforementioned essay about Instagram Boyfriends, I too have no confusion or doubt when I look back at smiling photos from vacations during certain periods of my life. I remember the underlying feelings and true memories beneath these photos, the miserable bickering in between taking 500 different photos to get the “best take.” It is both the technological and societal systems, interwoven together, that are to blame. The societal pursuit of status games is hard coded into our new tech.

And so it is not solely our memories, but our morals, that define who we are. The University of Arizona and Yale have conducted studies on Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative disorders showing that even through amnesia or lost memory capacity, the ability to retain consistent moral characteristics and behavior like honesty, compassion, integrity and generosity all seem to keep others’ perception of an individual’s identity and who they are consistent, versus starting to view them as a stranger. As cognitive neuroscientist Bobby Azarian concludes about the studies, identity is not just what we remember, “but what we stand for.”

This is the Fallacy of Infinite Memory. What’s the point of its pursuit if we lose our morals along the way? And our ability to be fully present within a moment and to each other?

In Closing : Feeling Seen

How do we regain open vulnerability and intimacy to feel fully seen?

How do I be all of me? We spend so much energy exploring and untangling this question because ultimately, we all have this innate human need and desire to feel seen and understood.

Despite all the challenges and side effects we experience online, there is so much opportunity for playing with Identity R&D that can help us become better, fuller people.

The Proteus effect is a phenomenon where by embodying an online avatar and its characteristics, it starts to change the behavior of the individual offline. The phenomenon is named after the ancient Greek god who could shapeshift into any form he wished. Studies show that taller avatars can increase our confidence offline, more attractive avatars can make us warmer and more social, older avatars can make us more fiscally responsible, and physically fit avatars can make us exercise more.

It sounds obvious, but I think we often need the reminder that who we see and interact with online is not always the full picture. The same is true in reverse for our offline identity(s) too. We are always on the outside looking in – we don’t truly know if who we are seeing means we’re understanding the full story.

A since deleted tweet by @rafathebuilder about the multitude of ways we express our identity, publicly and privately, online and off, struck me as the most important point of this entire reflection on identity — “What if intimacy is not knowing the most secret, but knowing them together?”

This rings true for me. The people in my life who I feel most connected to and most love for and from are all people who have the fullest visibility into my multitudes of self. I feel fully seen, without judgment. The irony is that the best result of the period where I experienced the most Digiphrenia, juggling multiple pseudonyms and digital communities, was when I started integrating online connections to offline life and friendships. Many of those friendships that started online pseudonymously have gone on to become some of my closest offline friends now, because we see and understand each other's multidimensionality. After all, the word “identity” is originally derived from the Latin word “idem,” meaning “same,” and the mid-16th century French definition of identity is the relationship between one's sense of self and its sameness with others. It is the exposure of our sameness that allows us to feel belonging – meeting in the gray space between personal identity and collective identity.

The contradiction of our current era is that our most open spaces are where we’re most closed off from our full selves, and our most closed spaces are where we can be most open.

The public arena of social media is a battleground between our most Compressed Identities. But it’s in private DMs, small group chats and offline conversations that I often find the most open and insightful conversations that show me who people are and how they want to be seen. Spaces most encoded with physical and psychological safety.

If we continue to barrel down our current path, squeezed between our algorithmic and societal systems, playing this zero sum game of status, attention and individualism, we risk continuing to slip into Identity Dysmorphia, using our loved ones as camera people and having meltdowns about hiding a dozen secret finstas.

“We are more connected to our own sub-identities than we are with each other. Let me step into my NBA self and read what people are saying about the game. Let me step into my CEO self and read a HBR piece. Let me be a parent and call my kid’s school. In none of those situations am I actually interacting with another person. I’m just acquiring and consuming and transacting with other people in those states. Yes, I’ve talked to six people. But nothing about my physical being has changed. Nothing has happened except in my head the entire time. That’s a common day. That’s basically every day.”

The future of identity presents a lot of provocative promises for multiplying ourselves through Profilicity and expanding our artificial Infinite Memory, sure, but the most beautiful and urgent opportunity in front of us is to harness the full potential of our online and offline spaces for open vulnerability and intimacy, to better be fully seen and understood not only by others, but by ourselves.

Recommended Reading

Artificial Memory & Orienting Infinity, by Kei Kreutler on Summer Of Protocols

Being Your Selves: Identity R&D On Alt Twitter, by Aaron Z. Lewis on Ribbonfarm

Extended Self In A Digital World, by Russ Belk

Identity Century, by Tracey Follows

Myself & I, by Safy-Hallan Farah on Real Life Mag

Our Decentralized Selves: Creating In A Post-Identity Future, by @itstheelword & @rafathebuilder on ZORA ZINE

Our Online Identity Crisis, by Matt Klein

Resisting Audience Capture: How to Maintain Integrity & Sanity Online, by Matt Klein on ZINE

The Extreme Self, by Douglas Coupland, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Shumon Basar

The Difference Between Dissociative and Alternative Identities, by Katherine Dee on Default Wisdom

The I In The Internet, by Jia Tolentino on CCCBLab

The Lore Zone, by Tiger Dingsun & Libby Marrs on Other Internet

The Post-Individual, by Yancey Strickler

Nick Susi is a writer and strategy executive, exploring the forces - technological, societal and psychological - that shape our identity, perception and culture. He has led strategy for dotdotdash, Complex, The Fader and Jay Z’s former media brand Life+Times. His research and writing can be found in Business Of Fashion, Friends With Benefits, Water & Music, Matt Klein’s ZINE, Joshua Citarella’s Do Not Research, Future Commerce and Boys Club.

Please do add: The Saturated Self: Dilemmas Of Identity In Contemporary Life - Kenneth Gergen, 1991

I tend to think a key word going unsaid here is narcissism.

Consciously monitoring your identity, and wanting other people to see it, is narcissistic. *Even* if the desire to not just be seen as one part of you, but every part. That's still an identity of sorts.

Also, here: "I know someone with a dozen secret finstas. I discovered that when they post on their main public account, they would spend hours logging in and out of their finstas to like and comment on their original post to boost the algorithm. This process in itself is not an issue. If you’re going to play the status games, play them well. But what was more puzzling was when I asked them about it, they denied it and had a meltdown"

Through a narcissism lens this isn't puzzling, right? The reason they are doing all the liking/commenting to support their identity as 'cool person'. And you pointing that out is exposing that they aren't their identity, which of course gets a violent reaction, because it's their goal to be seen how they want to be seen.

Which takes me to the main point: no one is their identity. Even this is a form of defense mechanism against that:

'We are forced to pick a singular lane and consistently craft our personal brand, package ourselves into a product and appease the repetitive, insatiable appetite of the algorithm.'

I agree people think this but ... forced? Easier than consciously admitting how much we want to be seen as our personal brand, I suppose.