magic, online!

how to navigate hyperreality

Special thanks to Alexander Boyce, Matt Klein, Andrew McLuhan, Ruby Justice Thelot and Nikita Walia for helping me develop this essay. All credit to Domingo Beta for creating the visual objects featured within.

Introduction : Is It Real Or Fake?

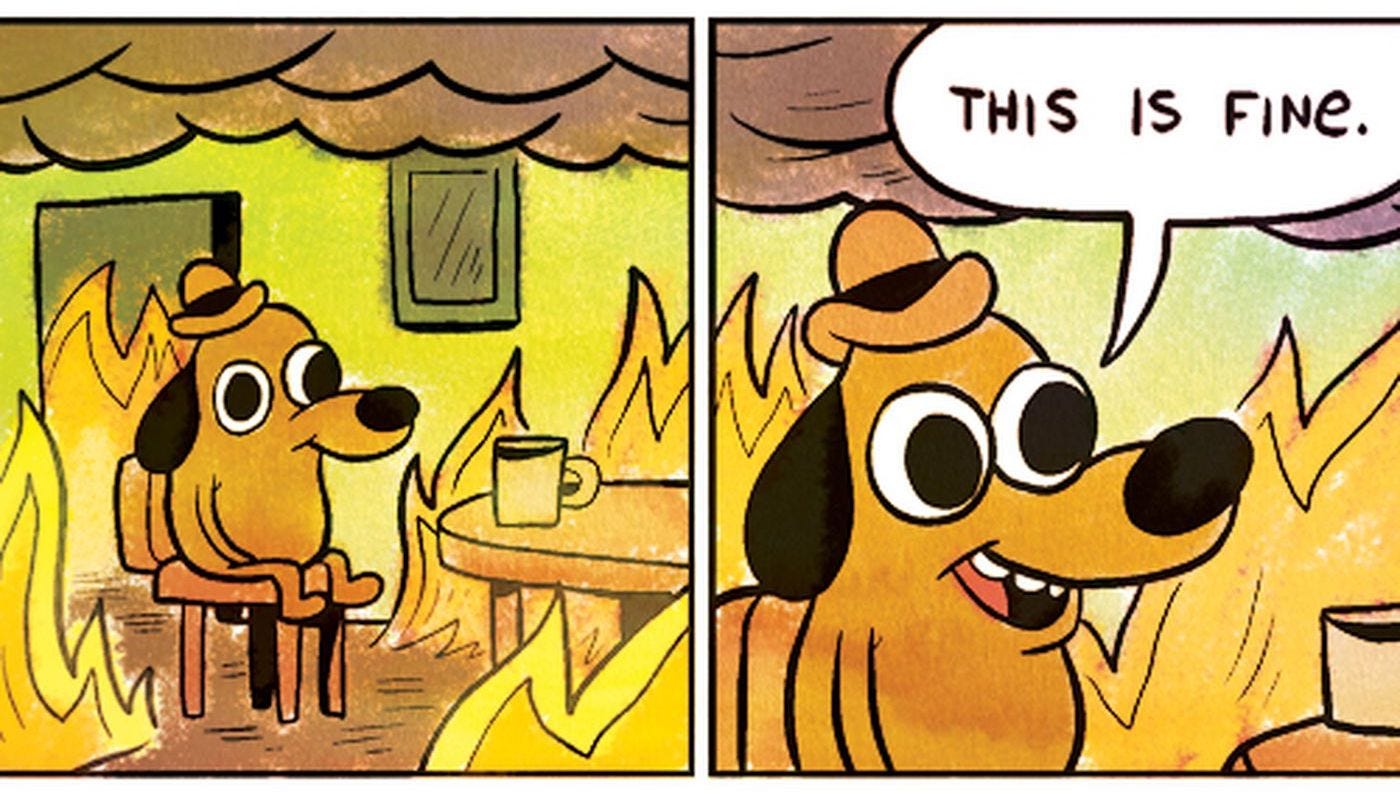

“Is it real or fake?” This question and debate is becoming more frequent in comments on social media. 2023 was another year of technological innovation, and the most notable – the acceleration of AI – feels like a deluge of daily magic tricks being practiced on us. Fake Drake & The Weeknd songs. Fake Keanu Reeves TikToks. Fake Popes in Balenciaga. Fake smiles in your photo memories. And now, fake robocalls from Biden. Mass anxiety, confusion and distrust are growing exponentially around the media we consume, especially with a consequential U.S. election less than a year away. How do we navigate this Baudrillardian hyperreal, post truth era we’re living in?

1 : Every New Wave Of Technological Innovation Is Accompanied By Magical Thinking

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles Of The Future

This question, “is it real or fake,” is as old as technology, electric media and magic itself. Similar to the “peak of inflated expectations” on the Gartner Hype Cycle, every new wave of technological innovation since the telegram has come with magical thinking.

Telegraph — 1840’s — The teen Fox sisters sparked a movement of spiritualism and seances by claiming to communicate with spirits through morse code-like tapping (Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media).

Image Projection — 1860’s — The invention of the Pepper’s Ghost theatrical illusion contributed to the cultural belief that ghosts are translucent (Lidia Zuin).

In-Ear Headphones — 1890’s — Within a few decades of the invention, a new wave of mentalists and televangelists used earpieces to trick people into believing they could read minds.

Film — 1900’s — The Great Train Robbery allegedly caused panicked reactions amongst audiences, believing the train may careen out of the screen into them.

Photography — 1910’s — Two young girls claimed to capture images of the Cottingley Fairies in their back garden, sparking new popularity and debate about spiritualism.

Telephone — 1920’s — Thomas Edison attempted to create a “spirit phone” that could communicate with the dead.

Radio — 1930’s — Orson Welles presented his infamous War Of The Worlds broadcast, causing some listeners to panic that martians were invading the earth.

Internet — 1990’s — A surge of new spiritual beliefs grew, where people believed that cyberspace was a gateway to transcendence (Lidia Zuin).

These historical patterns show us it is entirely human to turn to the supernatural, conspiracy, spiritualism and the occult in our effort to make sense of how new technology and media might change us, both individually and collectively. It is one big cope, to regain a sense of control in a time of uncertainty and difficulty.

As each new innovation cycle becomes faster and more frequent, it could mean each period of magical thinking will blur and overlap with the next. As more people see others adopt magical thinking, social proof tells us that it could grow into a mass sociogenic illness that’s culturally normative to a group and a period of time – an epidemic of collective delusion.

We are so quick to publicly judge and dunk on others in this state, but this is an entirely human experience that we are all susceptible to. Consider how, according to Anil Seth, our brains construct our perceived reality through constant prediction and controlled hallucination. It’s like autocomplete for our brains. When we drink a glass of water, we immediately feel hydrated and refreshed, even though our body doesn’t actually process that water for hydration until much later. Prediction, controlled hallucination.

The debate over “is it real or fake” is somewhat ironic, because so much of what we experience as reality even within our own bodies is actually simulation.

This is a call to shed our hubris, recognize our quite normal human vulnerabilities and embrace radical humility and empathy for ourselves and each other. The good news is, we’ve been here before. While the current flavor of AI doomerism is new, this question of reality is not. We no longer think we can communicate with the dead through morse code or telephones, or that the earth is being invaded by aliens when listening to the radio. What looks like a mind blowing card trick the first time could look like simple sleight of hand the twelfth.

2 : We Are Illusionists With The Ability To Shape Our Reality

“Every society has its magician, its illusionist. [...] This function in modern society is now occupied by the Techno-Evangelist. The individual capable, for their own gain, of transfiguring an ordinary object into a magical one through the power of narrative.”

We say everyone is a creator now. But I say everyone is an illusionist. We have become masters of manipulation through media and narrative. We often think of magic as supernatural power, but it’s also sleight of hand, misdirection and a controlled point of view. What we see and don’t see shapes the reality tunnel we perceive before our eyes, which in turn shapes our physical, lived action.

How media and narrative blurs “what is real or fake,” is not new. In the Roman Empire (since we’re thinking about it so often), bread and circuses were created by the ruling class to feed the masses superficial comfort and entertaining spectacles in the colosseum to generate public approval, while diverting attention away from the realities of their power and control. In the twentieth century, Edward Bernays pioneered applying propaganda to business. He used spectacle to transform cigarettes into a symbol of freedom and equality for women, which over the past 100 years, has become the foundation of the hypernormalized constructs of public relations and consumerism that we know today. In Mythologies, Roland Barthes discusses how wrestling (and now, politics) uses kayfabe, the convention of presenting staged narratives and spectacles as real to capture attention and elicit a desired response from an audience.

Pop culture narratives often question these hypernormalized reality distortions. In “The Rehearsal” and “The Curse,” Nathan Fielder exposes the secrets of these magic tricks. He satirizes the absurdity of how we stage and edit reality TV and reality-based media behind the scenes to construct narratives that manipulate the viewers’ perception (Terry Nguyen, Dirt).

As individuals we are just as capable of distorting our own truths. We construct our identity and reality through a series of narratives that we repeat to ourselves and each other over and over again, online and off, until they become real. We are all LARPing. We influence and control how we’re seen to shape future outcomes for our personal and professional lives.

We often lament about how social media is the problem, eroding society’s sense of truth and trust. But it’s also the solution. We take for granted there has never been a time in history like now where we as people have had more ability to create and distribute our own media and narratives with speed and scale. With organization, we have the power to shape our individual and collective realities in a way that only the ruling class previously was able to do.

The concept of hyperstition posits that within the techno-capital machine, a narrative, even if not real today, can become real through the self-fulfilling prophecy of its repetition over and over again, leading to real-world effects when adopted and acted upon by a group of people. A narrative by r/WallStreetBets day traders can boost the GameStop stock price and put a hedge fund out of business. Alternatively, online conspiracies by QAnon and Trump can lead to a very real insurrection. Is Peach Fuzz, and other Pantone colors of the year, an accurate prediction, or a self-fulfilling prophecy? These are our modern day spells and incantations.

“These are tricks at scale.”

Matt Klein

If we all have access to the magical potential of social media and AI tools in our pocket, what do we use it for? Are we feeding existing hypernormalized constructs, or are we creating the next 100 years of new realities that better serve us? If we assume every person we see online has the power of an illusionist, how does that reframe how we approach our online interactions, and challenge our present default that everything we see is real and true?

3 : Magic Requires The Right Kind Of Skepticism

“We’ve arranged a society on science and technology in which nobody understands anything about science and technology, and this combustible mixture of ignorance and power sooner or later is going to blow up in our faces. I mean, who is running the science and technology in a democracy if the people don’t know anything about it.”

The history between magic and skepticism are intertwined. Understanding the distinction between different types of skepticism is key to our hyperreal, post truth era.

Magicians are masters of reality distortion. It would be so easy to manipulate their audiences beyond entertainment, for personal gain. Yet, throughout history, many of the greatest magicians have been the foremost leaders of movements of scientific skepticism. They demystify “what is real or fake” and self-regulate for bad actors to protect the public from exploitation.

The inventor of Pepper’s Ghost – the same technique used to create Tupac’s Coachella performance in 2012 – used his knowledge to teach others how to debunk claims of communicating with ghosts. Harry Houdini gave lectures, wrote articles and books, even testified before Congress to expose false mediums and seances exploiting grieving families. James Randi appeared on The Tonight Show throughout the 70’s and 80’s to expose psychics and mind-reading televangelists. Penn & Teller used to host a debunking docu-series called Bullshit! too.

Our hyperreal, post truth era, however, attracts pseudoskeptics in droves. Their narratives are largely constructed around questioning truth. These narratives resonate extremely well because as truth and hypernormalized constructs collapse around us, that feeling of disorientation is very real. In Doppelganger, Naomi Klein aptly states, they “get the facts wrong, but often get the feelings right.” This breed of skepticism pushes those in a vulnerable state of crisis deeper into magical thinking and conspiracy. Further, as crank magnetism shows, it can mutate magical thinking about an isolated belief into an entire identity.

“It is the responsibility of the new technologist to make others aware of what technologies and media do to them.”

We as creators of technology and media are intimately acquainted with the mechanics of reality distortion. What is our responsibility? In the wake of AI acceleration and increasing disinformation, calls for better media literacy grow louder. But it feels empty, not so different from politicians offering their thoughts and prayers after a mass shooting. How are we leveraging our skills, knowledge and investments? Better informing everyday people about how to navigate this disorienting time, or further mystifying audiences through magic tricks and spectacles? Where is our equivalent of Virgil Abloh’s Free Game for media literacy and cognitive security?

4 : We Can’t Fight Attention With Attention

There is a wrinkle. You can’t beat someone who is seeking attention by any means necessary by giving them attention. This is the paradox of our attention economy. Trying to debate pseudoskeptics on “what is real or fake” often doesn’t matter nearly as much, because the attention game has already been won.

When James Randi exposed both psychic Uri Geller and televangelist Peter Popoff on The Tonight Show, both ultimately bounced back and the attention propelled them further towards more TV appearances, supporters and fortune. All parties benefited from and fed off the attention in both directions.

Similarly in politics, The New York Times reported that in 2016, major news organizations gave Trump’s campaign close to $2 billion of media attention, about twice the all-in price of the most expensive presidential campaigns in history. When George Santos was expelled from the House, he immediately went viral on Cameo and on Ziwe’s interview. She asked him how to make him go away. He himself knows the answer – “Stop inviting me to your gigs.”

Even writing about them now keeps them in our attention. There’s a tension between how to call out disinformation, underlying systems and root problems, without legitimizing or drawing unnecessary attention to the personality or information. Disinformation researchers at Stanford have studied how other viral diseases like Ebola spread. Like any virus, we must reduce exposure and quarantine sources of infection. The more attention we give to magical thinking and pseudoskeptics, the more we may risk the susceptibility of others.

We need to interrogate our own actions. Is our primary reaction true understanding more than impulsive sharing, or the reverse? What are we giving our attention to? When creating and sharing, what are we asking others to give their attention to? As with hyperstition, does the debate over whether or not something is real give it the disproportionately amplified attention it needs to ultimately become real?

Closing : A Reality Check On Coexistence

As hyperreality persists, we risk feeling helpless and out of control. But we must resist the urge to check out and isolate ourselves on either of two polar extremes.

On one side, there is the full rejection of hyperreality. As our sense of sight fails us, we may ditch our screens and log off, seeking a new ratio of our senses (Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media). As trust erodes, we may turn to “Hyperlocal Global Skepticism” (Ruby Justice Thelot). We may enter a post-scale era, focusing on closed groups and natural environments within our physical proximity. We may place the utmost value on who we know and trust directly, as well as what we experience directly in front of our lived bodies. This resignation from digital society, however, risks limited information and echo chambers. As one culture encounters another that’s unfamiliar, collisions may cause conflict.

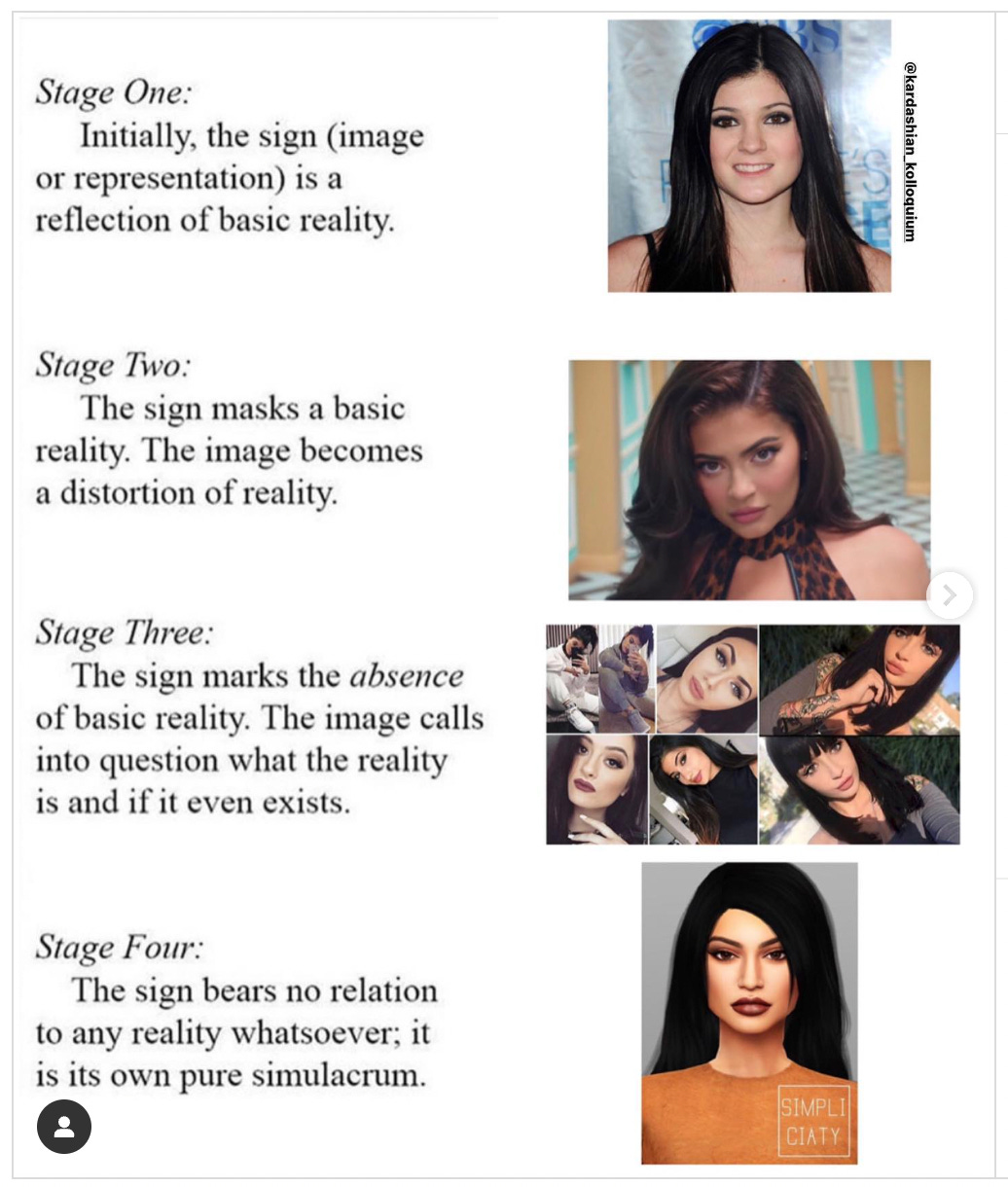

On the other side, there is the full embrace of hyperreality. There may be a decreasing desire to know or question reality from simulation. The line between human and technology may blur too. Neuralink is already on the horizon. We’ve already seen how a decade of digital face filters and Facetune have led to very real body dysmorphia and an increase in plastic surgery. Editing our digital selves and physical selves may carry little distinction.

Even Baudrillard himself urges us to resist this polarized radicalization.

“We have to fight against charges of unreality, lack of responsibility, nihilism and despair.”

We need a reality check. We need to let go of our hubris and bring each other closer together for connection, nuanced conversation and radical intimacy that can’t be flattened into a single social post. Our first instinct must be to listen, understand and see beyond our own reality tunnels to construct a more complete, coherent point of view. We must balance the pluralistic coexistence of multiple perspectives and narratives at once. Otherwise, we may see humanity, abracadabra, disappear.

Nick Susi is a writer and strategy executive, exploring the forces - technological, societal and psychological - that shape our identity, perception and culture. He has led strategy for dotdotdash, Complex, The Fader and Jay Z’s former media brand Life+Times. His research and writing can be found in Business Of Fashion, Friends With Benefits, Water & Music, Matt Klein’s ZINE, Joshua Citarella’s Do Not Research, Future Commerce and Boys Club.